What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

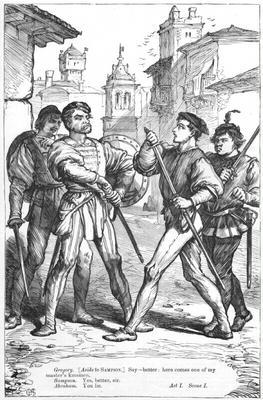

Are ever thrust to the wall: therefore I will push

Montague's men from the wall, and thrust his maids

To the wall. William Shakespeare – Romeo and Juliet Act 1 Scene 1

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

What is this?

The Genius annotation is the work of the Genius Editorial project. Our editors and contributors collaborate to create the most interesting and informative explanation of any line of text. It’s also a work in progress, so leave a suggestion if this or any annotation is missing something.

To learn more about participating in the Genius Editorial project, check out the contributor guidelines.

At this point, everyone is tired of the Capulets and the Montagues fighting.

Clubs, bills and partisans are all kinds of weapon (the last two are forms of halberd).

Here, they’re used to refer to the people who carry them, as in “Halberds, this way!”.

You can see the social distinctions in the weapons. The nobles and their retainers all carry swords. The common citizens wield street brawl arms (clubs) or infantry weapons (bills and partisans).